Tim Jordan, Commissioner

Keynote address, ENA Regulation Seminar 2025

State Library of Queensland, Brisbane

Good afternoon and thank you for inviting me to speak to you today.

I’d like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we meet today and pay my respects to Elders past and present.

And I’d like to recognise the Aboriginal artist and designer behind this artwork, a local Brisbane woman, Elaine Chambers-Hegarty.

With a career spanning 30 years, Elaine has designed artwork for many organisations, including the Brisbane Broncos and the Institute of Urban Indigenous Health.

She is passionate about fostering connection and engagement with Australia’s First Nations culture and I think you can see the hope and vibrancy in her work.

So, why is transport decarbonisation so important?

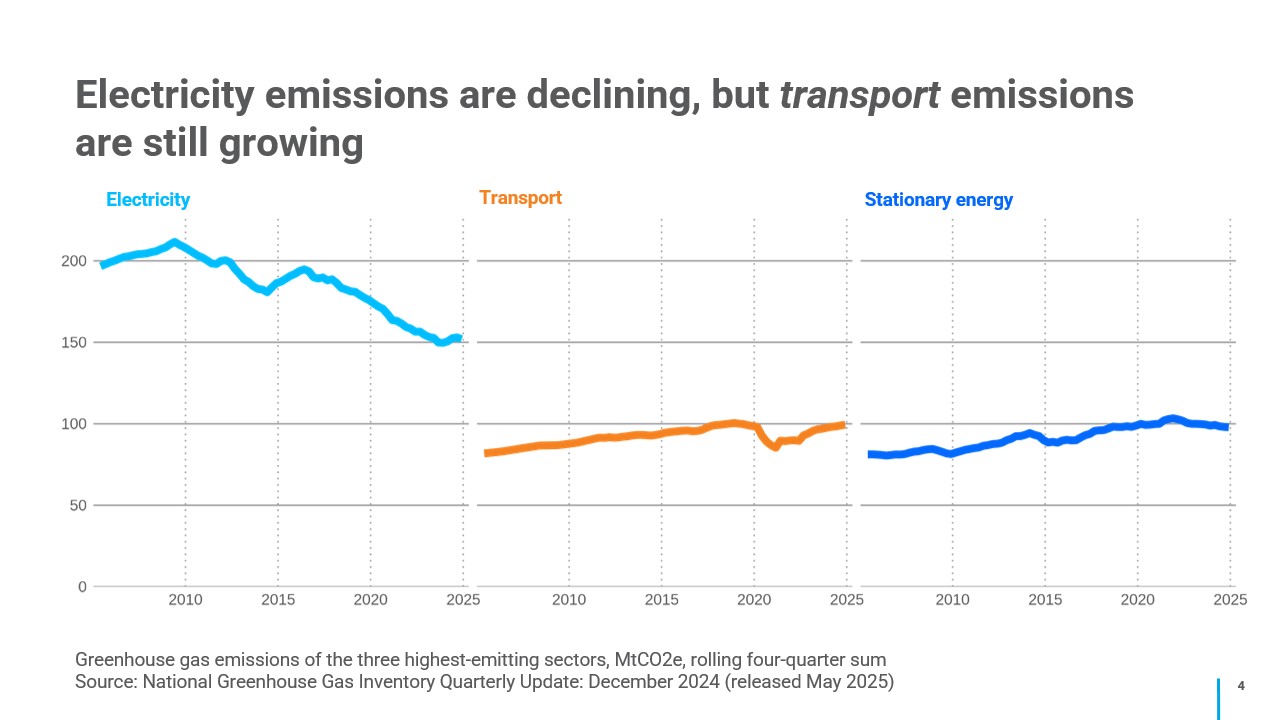

These charts show emissions in Australia from the three highest-emitting sectors.

If we look at electricity emissions over the past 20 years, they’ve fallen by about a quarter since 2005.

They have plateaued recently, but we can expect them to decline rapidly as coal exits and we move to a high-renewables system.

Non-electricity stationary energy emissions – the series on the right here – appear to have peaked earlier this decade.

Most stationary energy emissions are subject to the safeguard mechanism, so this series should decline, depending on the extent that emitters use offsets.

But, transport emissions, which have grown by around a fifth since 2005, are still rising.

We saw a dip during COVID, but it appears transport emissions are back to trend growth.

They’re now the second largest source of emissions in our economy and projected to become the largest source by 2030, as electricity emissions continue to decline.

So, transport emissions are growing and there’s no sign of a turnaround. That's a real problem and we need to address it.

As I said in my opening, the main path to decarbonising transport is electrification. We need lots of electric vehicles.

Rapid EV uptake is necessary for us to achieve net zero by 2050.

At least two-thirds of all vehicles must be battery EVs by that time to meet those objectives, on AEMO’s numbers.

But we’re a long way from that. EVs currently make up 1.5% of Australia’s vehicles, and they account for less than 10% of new car sales.

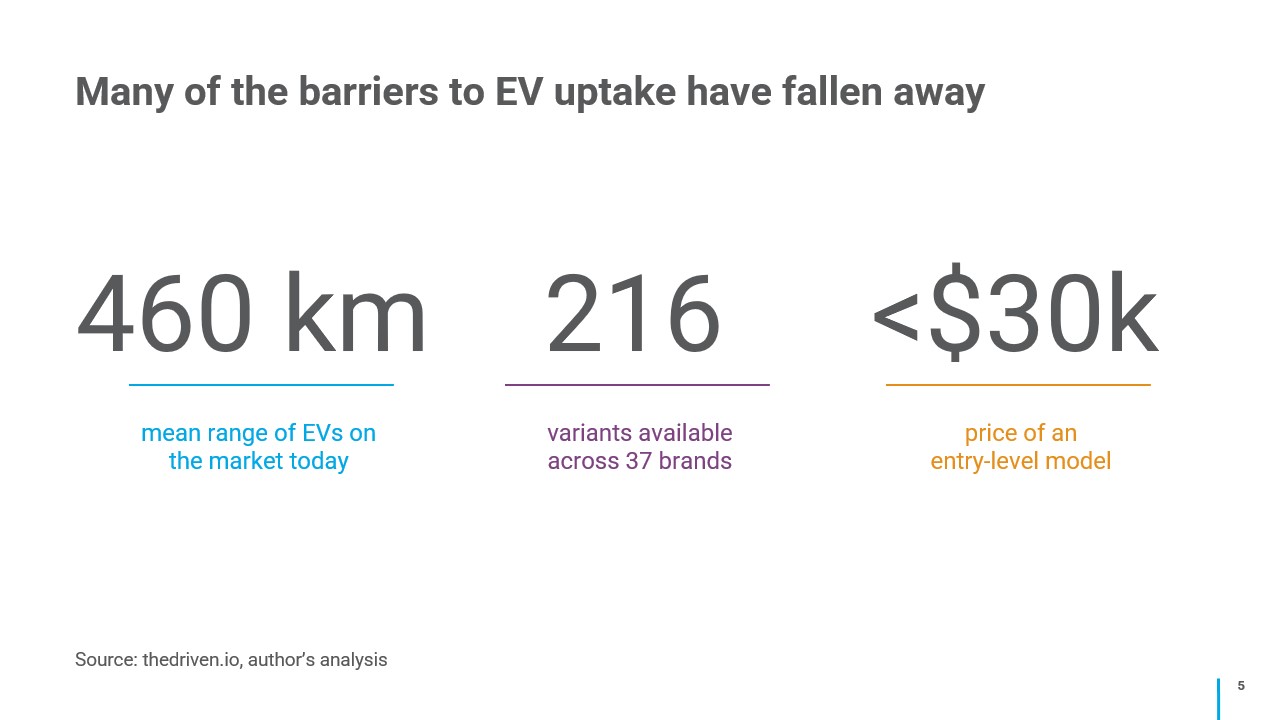

Many of the barriers to EV uptake – such as range anxiety, model availability and affordability – have fallen away.

One of the big impediments to buying an EV in the past was the concern about just how far down the road you could go before you’d need to plug it in.

Ten years ago, that number was something like 100 kilometres, turning the Aussie summer road trip into a logistical nightmare.

Better batteries mean EVs on the market in Australia today have a mean range of around 460 kilometres. Some new models can go more than 600 kilometres on a single charge.

There is now a much wider choice of models, including low price EVs.

Drawing from a list on The Driven, there are now something like 216 variants on the market here, across 37 brands.

And the price differential between EVs and internal combustion engine – or ICE – vehicles is narrowing.

The International Energy Agency’s 2025 Global EV Outlook says today’s EVs often have a lower total cost of ownership than ICE cars over the life of the vehicle, thanks to lower fuel and maintenance costs.

The IEA points to falling battery prices, market competition and economies of scale to explain the strides in EV affordability over the past decade.

It means that in some cases, the sticker price for an EV is lower than a comparable ICE car.

In China, for example, nearly all small EVs in China were priced below the average small ICE car last year, with the average purchase price about half that of the average small ICE car.

This led to the almost complete electrification – nearly 95% – of small car sales in China in 2024.

The IEA says the availability of a wide range of affordable EV models will be key to unlocking mass-market adoption.

It notes that the EV range is skewed to higher end models in the US and Europe.

But we are seeing more affordable EVs entering the Australian market, with the cheapest entry level model priced below $30,000. There is also a growing second-hand market.

With these barriers coming down, Australia’s electric car fleet is starting to grow. But not very fast.

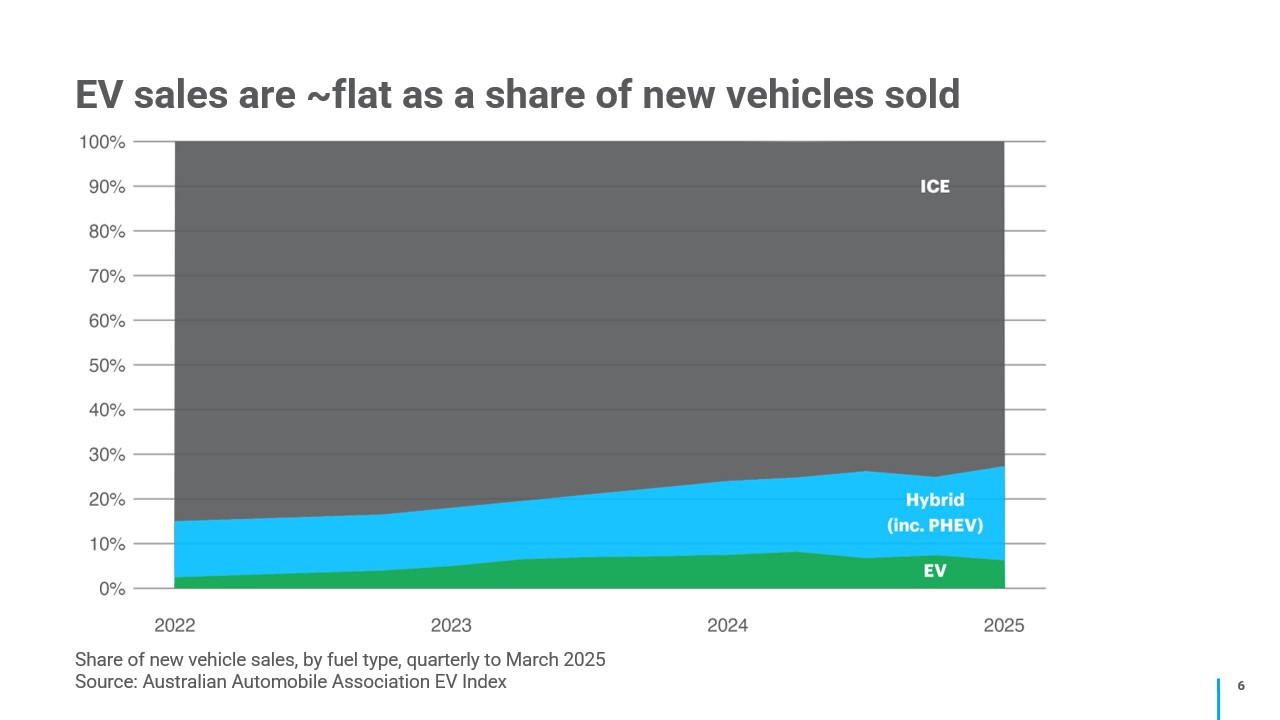

Recent EV sales in Australia are flat as a share of new vehicles sold.

Indeed, data through to March this year shows EVs share of sales declining.

There have since been reports of an uptick in the June quarter – but, even so, this is not the rate of sales we need to decarbonise our transport sector.

Data through to March from the Australian Automobile Association shows while the share of ICE vehicle sales is falling, the growth is in hybrids.

Hybrid and plug-in hybrids sales have grown from around 7% of new cars in the first quarter of 2023 to 21% in the first quarter of 2025.

On the other hand, battery electric vehicles remained at around 6% over that period, with a bump as drivers took advantage of government rebates, which have now ceased.

So, in pure EVs, which have to be the long-term answer for the transport sector, we’re not seeing the growth that we need to meet our net zero objectives.

ICE vehicles still make up the vast majority of Australian car sales.

Australia’s EV take-up is well below the global average of 18%.

So, if prices are coming down, the choice of EVs is growing and range anxiety is falling away, why aren’t EV sales increasing to the extent we need them to?

Without doubt, lack of public charging infrastructure is a factor.

This was borne out by the Consumer Policy Research Centre, which surveyed 2,000 Australians in 2022 about the barriers and potential enablers of EV take-up in Australia.

Almost a third of respondents said lack of access to EV charging infrastructure, both at home and on a trip, was a barrier.

About 1 in 5 people identified journeys becoming difficult to plan due to uncertainty around charging infrastructure.

In addition, structural barriers such as renting and apartment living were identified as limiting access to EV charging infrastructure.

This highlights the need for public EV charging facilities.

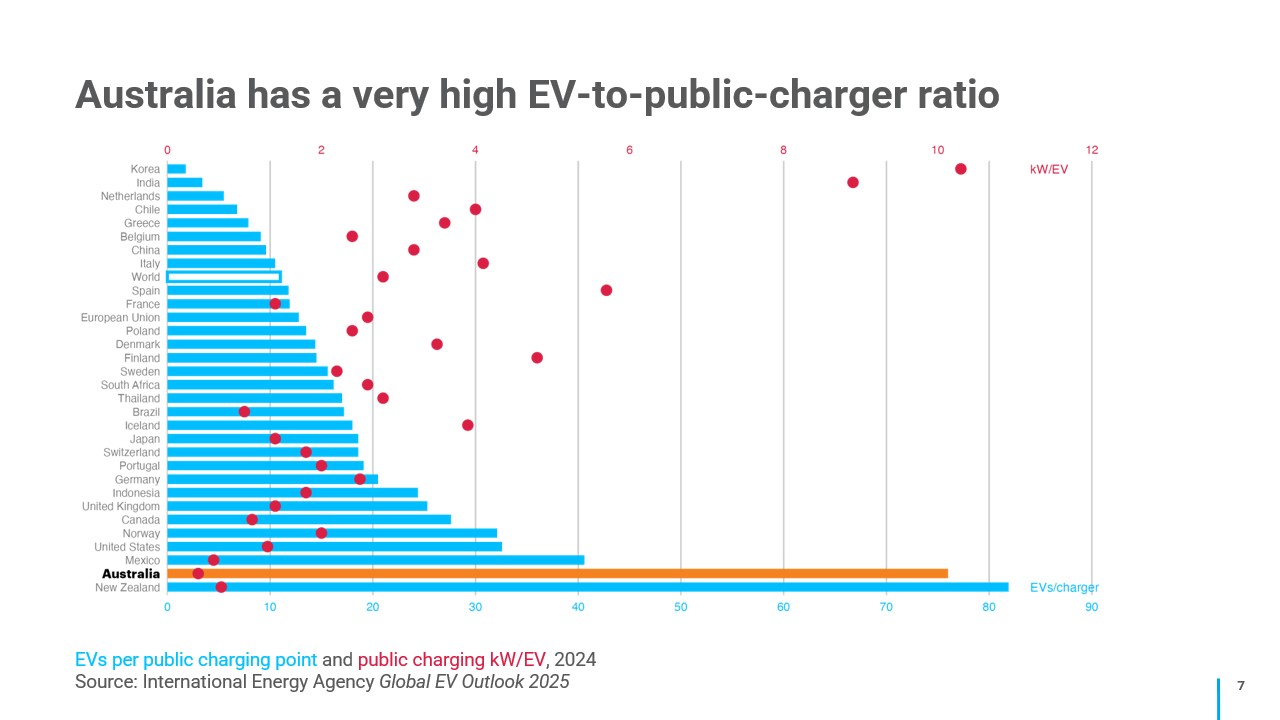

And Australia, along with New Zealand, is clearly trailing the world in this area.

Indeed, our two countries have the world’s highest EV-to-public-charger ratio.

Australia has 76 EVs per public charger, compared to a world average of 11. South Korea leads the world at the moment, with about 4.

And, as the red dots show, we also have the lowest public charging kilowatts per EV.

Some charge point operators contest these claims, arguing the lack of charging infrastructure is not as bad as the IEA figures suggest.

However, it is clear we could be doing more.

According to the Electric Vehicle Council, Australia has fewer than 2,000 public chargers at just over 1,000 locations across Australia.

This was a 90% increase on the 2023 levels but as we’ll see, this is unlikely to be enough to support the massive acceleration in EV sales we need to meet carbon targets.

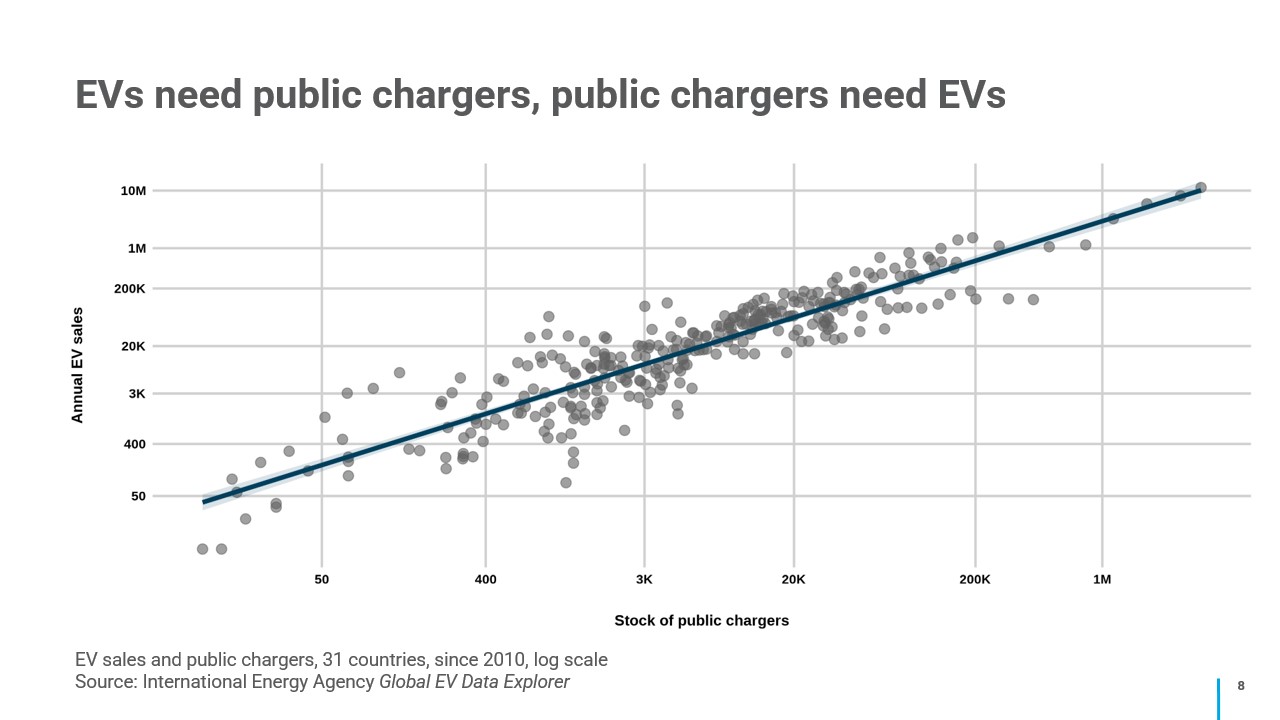

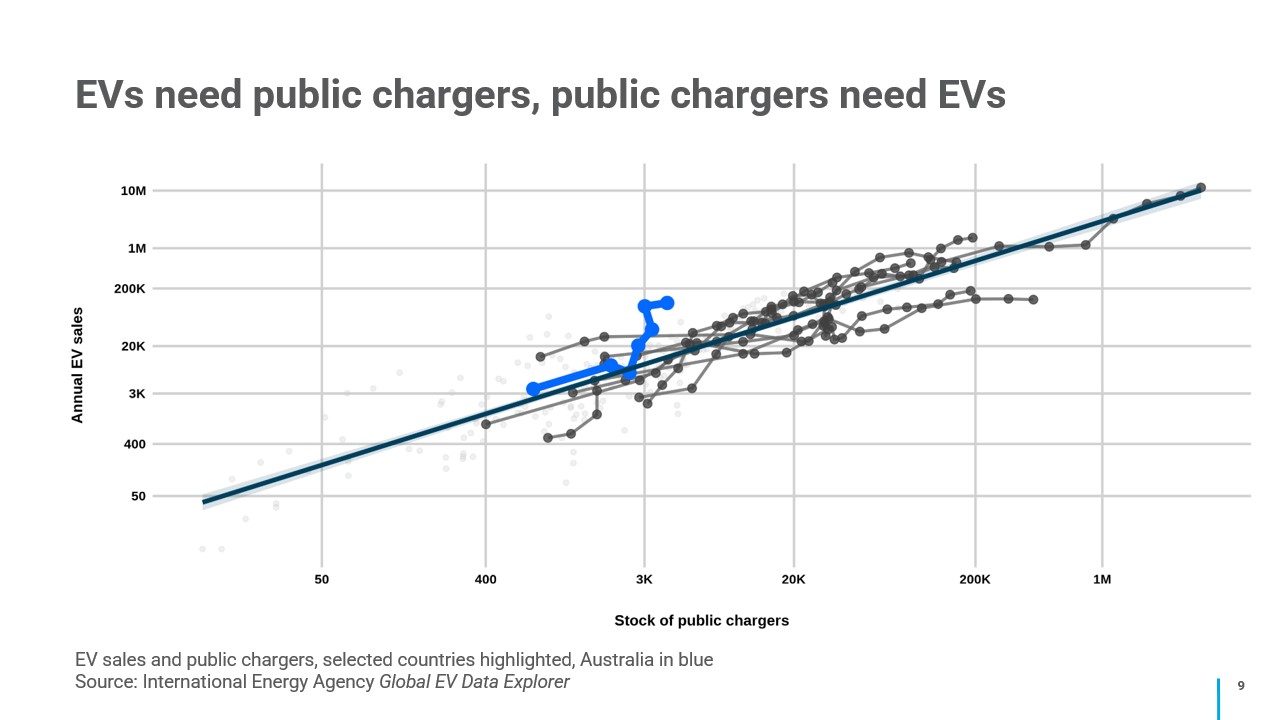

So, what’s the relationship between public charging infrastructure and EV sales?

I’m going to introduce a bit of tiny econometrics here to show that they move together.

This is a scatter plot of 31 different countries that shows annual EV sales against the stock of public chargers, going back to 2010.

The tight clustering around the line is evidence there’s a simultaneous relationship between EV sales and the stock of public chargers.

Each country has a set of dots. You can see the dots all head to the north-east. The more EV chargers you have, the more EVs you sell.

This chart includes global leaders in EV uptake such as Norway and the Netherlands, which have grown their public charger base to enable higher levels of EV uptake.

Bear in mind that about two-thirds of the growth in public chargers since 2020 has been in China, which is the dots out there in the north-east corner of the chart.

China, which now has about 65% of the world’s charging infrastructure – or 3.3 million public charging points – also has 60% of the world’s EVs.

What does Australia’s journey look like?

Well, here we are, the blue line on this chart.

And it shows we’ve actually had an uptick in EV sales, but we haven't made commensurate progress with our charging infrastructure.

This suggests a likely shortfall of public EV chargers – and creates the risk that our EV take-up is going to stall unless we build more, fast.

In other words, if the global pattern of simultaneous EV-charger deployment holds in Australia, we're going to have to build a lot of EV chargers to unlock the next level of EV penetration.

Public charging is a classic case of the network externalities problem. You could also think of it as a chicken-and-egg problem.

Start with the household side. People want convenient personal transport. EVs are on the market, at reasonable cost. But if they can’t charge them conveniently, they will buy a hybrid or an ICE vehicle.

Then, look at the charging infrastructure side. To earn a return on the charging infrastructure, a company needs to be reasonably confident that there will be EVs on the streets to charge.

The challenge is: companies won’t install chargers anywhere there aren’t lots of EVs already. But I won’t buy an EV unless I’m reasonably confident that I can charge it anywhere I might want to go.

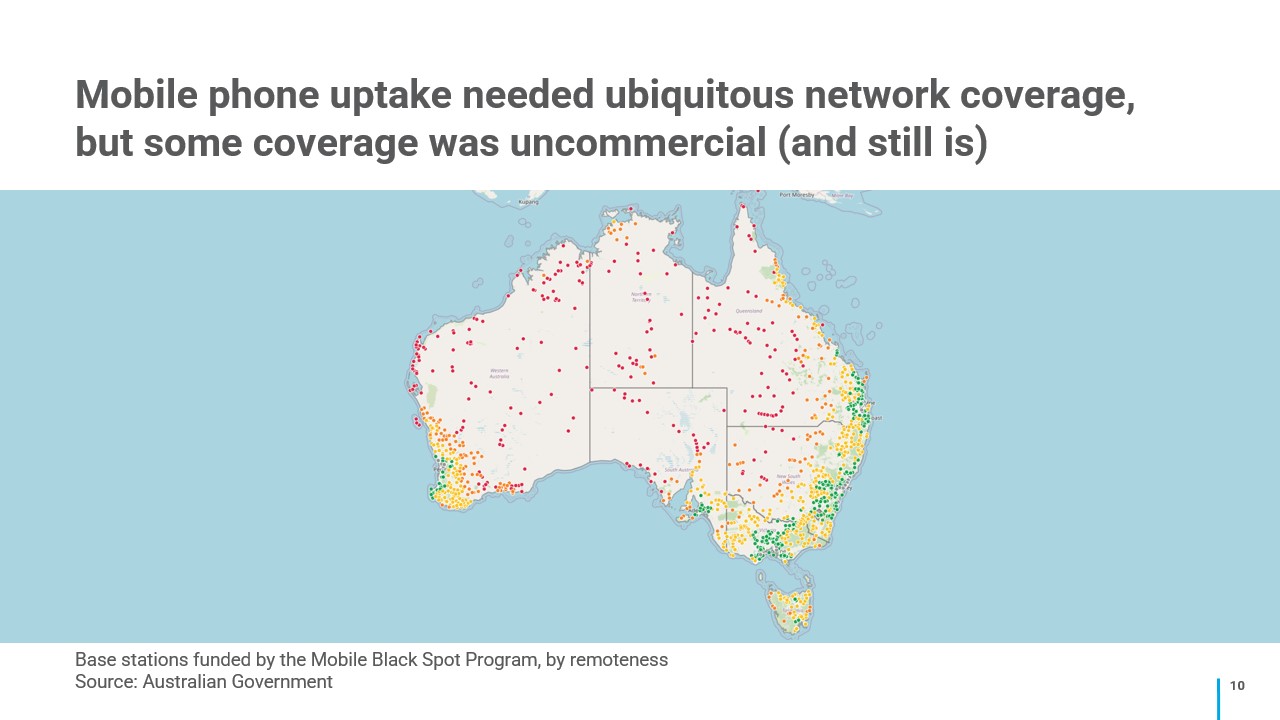

Think about the parallel with mobile phone infrastructure.

Mobile phone uptake required ubiquitous network coverage. Our phones are worth more to us if we can use them wherever we might go in the country.

But in many remote areas of Australia, it’s simply not commercial to build the base stations required to provide that coverage.

So, the Australian Government has subsidised mobile phone towers in those areas to ensure that ubiquitous infrastructure coverage, and overcome the network externalities problem.

As a result, Australia has been a leading adopter of mobile phone technology and has one of the world’s highest rates of smartphone ownership and usage per capita.

Similarly, our EVs will be worth much more to us if we can take them anywhere across the country and be confident we can charge them.

That will drive increased demand for EVs, and in turn increases support for more chargers.

You can see how this creates a virtuous circle.

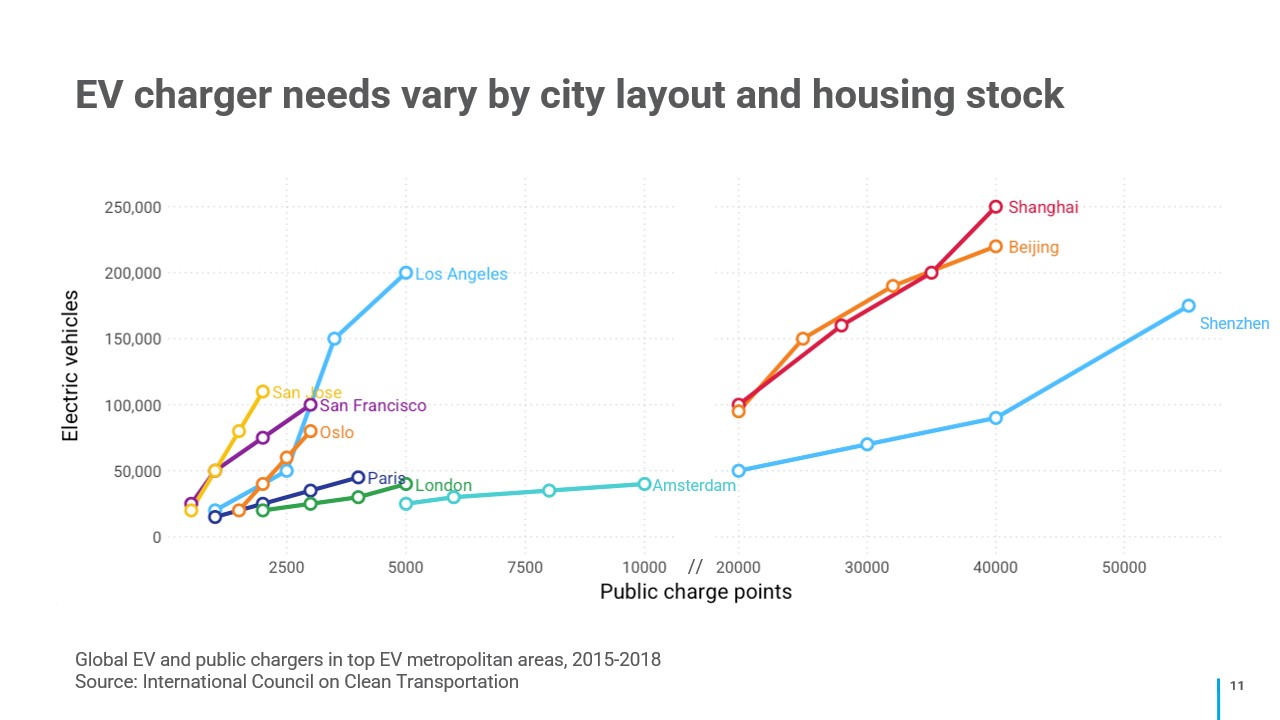

So can we just take the chart showing the relationship between EV sales and the stock of chargers and figure out how many chargers to build?

Not exactly.

Complicating the picture is that fact that EV charger needs at the city level vary depending on a range of different factors.

In China’s densely populated cities, many drivers rely on public charging points, whereas in Europe, access to home chargers is far higher.

Across Australia, there are a range of geographies and population densities that will determine the extent of charging infrastructure required.

Home charging remains the most popular way for people to charge their EVs. And that section of the market looks after itself.

But more public chargers are needed to support mass adoption of EVs among segments of the population without access to home chargers.

This includes people who don’t have off-street parking and those living in multi-family dwellings.

The vast majority of Australians live in cities.

But the population density and the configuration of dwellings in our cities varies widely by suburb and street.

Given these factors, we need an approach that delivers the right number of chargers in the right places.

We need to be sensitive to local conditions, or we risk over-building or under-building the charging infrastructure we need.

That said, we will probably need a lot of chargers.

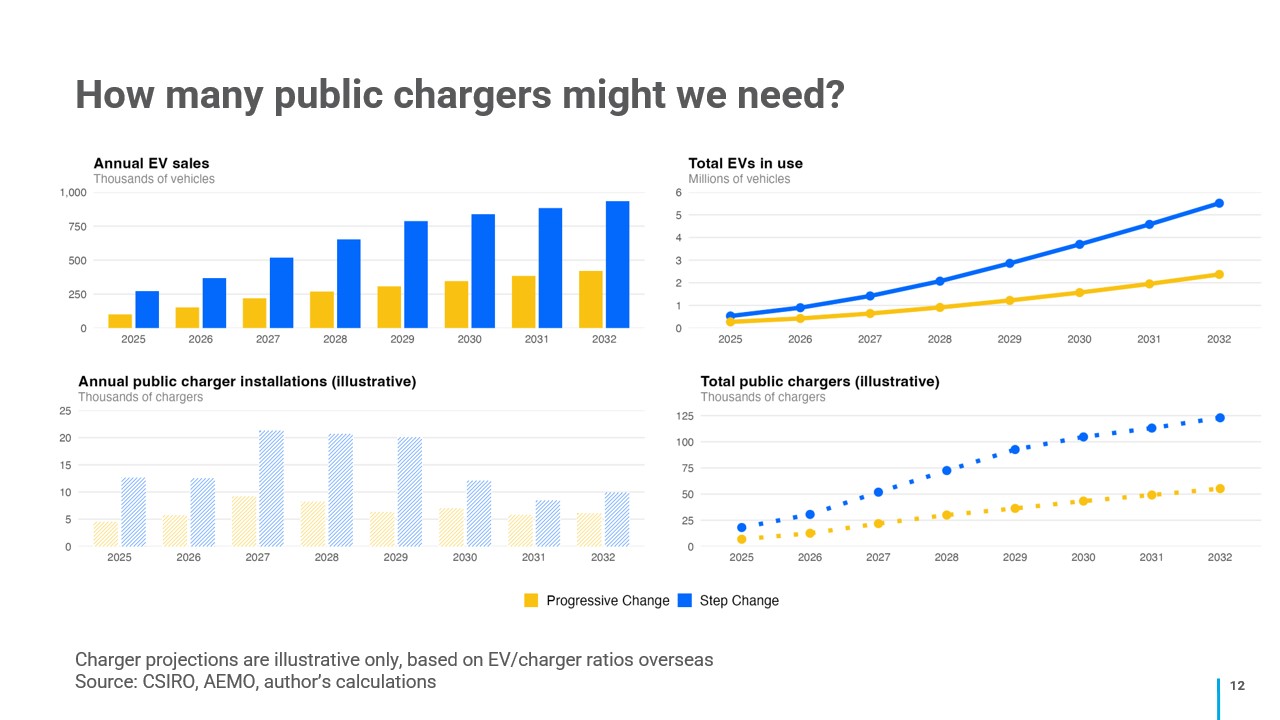

If we look at the EV uptake pathways from CSIRO reported in AEMO’s Integrated System Plan, the need for a rapid buildout of publicly accessible chargers is stark.

The lower two charts take international ratios of EV-sales-to-public-chargers and impose them on CSIRO’s projections of EV uptake.

That approach suggests we could need somewhere between 5,000 and 20,000 new public chargers each year for several years, depending on the uptake scenario.

This is not a forecast – it’s just the arithmetic of charger numbers based on ratios overseas and the number of EVs we need to add each year to meet our carbon goals.

But it usefully illustrates the scale of the challenge. It’s a big number, particularly when you consider we’ve got only a few thousand public chargers to start with. Installation rates would need to scale up dramatically.

So, it’s an issue we need to get moving on quickly to make up the gap to get more EVs into the market.

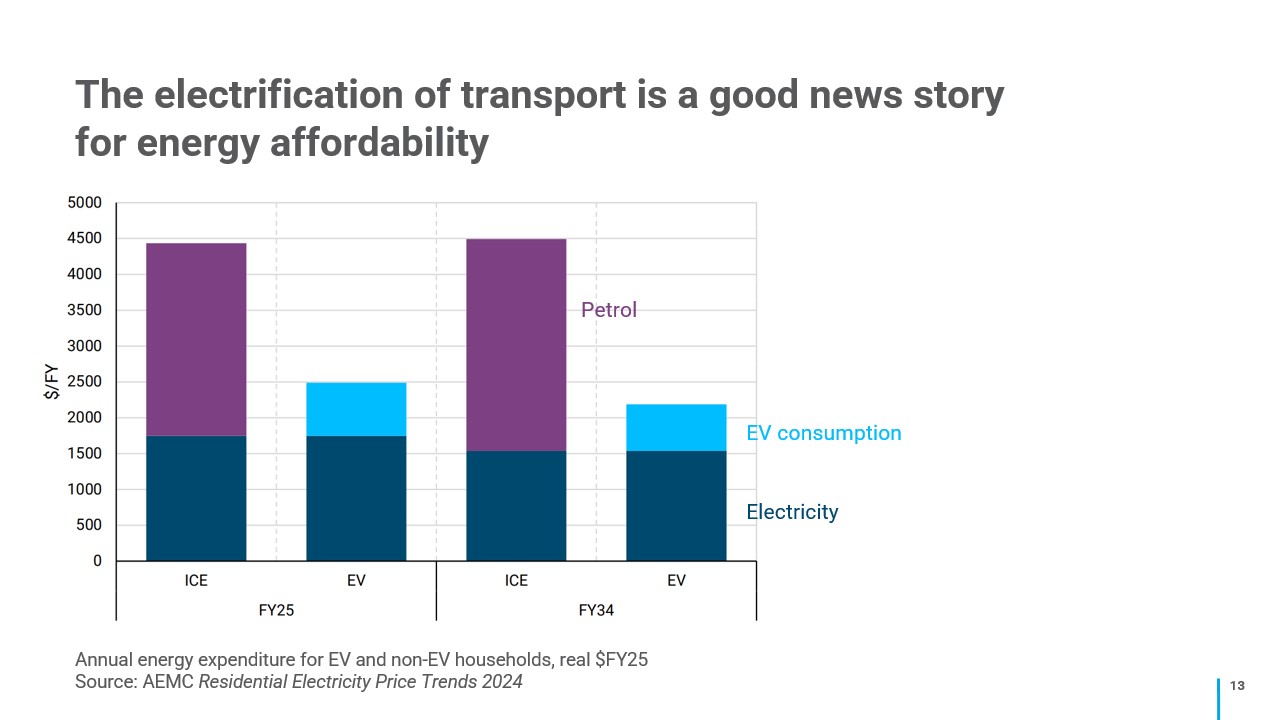

At the end of the day, the electrification of transport is a good news story for household budgets.

We released an analysis in November last year, showing how Australian households could significantly reduce their total spending on energy over the next decade through a well-managed transition to electrification.

By far the biggest saving go to consumers with an EV, who could save around $2,000 a year.

These cost savings do not rely on a consumer having to fully optimise their charging to low price periods.

The electricity costs of running an EV have been calculated on the basis that the household charges their vehicle when it’s convenient to them, rather than only during the day when electricity costs are low.

As we said in the report, access to EV charging is needed for households to realise these cost savings.

I know there are a lot of strong views on this subject, so I want to leave some time for questions and comments.

As I said at the outset, I’m not here to advocate for a particular way of accelerating the infrastructure rollout, but rather to contribute to the conversation.

Because getting the right charging infrastructure in place is an urgent issue to address.

There’s a school of thought that says we need to create a competitive market for EV charging infrastructure.

Competition is a powerful force for delivering for consumers. But I see the greater issue is the need to decarbonise transport, which will require a lot more EVs on the road and a much quicker uptake than we’ve seen to date.

So, I come from the perspective of how do we deliver that growth? And to me, deploying kerbside chargers quickly is fundamental to that.

I hope I’ve provided some food for thought and I’m happy to open this up to further discussion.

Thank you.