Sally McMahon, Commissioner

6th High-Level Meeting of the Electricity Security Advisory Board, International Energy Agency

9 Rue de la Fédération, 75015, Paris

Good morning everyone,

It’s such a pleasure to be here in person and to have the chance for real conversations with you all — not just about the differences between our nations, but about the common challenges we face as we navigate the energy transition.

My name is Sally McMahon, and I’m a Commissioner at the Australian Energy Market Commission, or the AEMC.

For those who may not know us, the AEMC is an independent statutory body. We are responsible for making and reviewing the national energy rules and for advising Ministers. Put simply: our job is to make sure all the moving parts of our market system continue to work effectively, and that changes happen through robust governance and consultation.

I think of the AEMC as the steward of Australia’s energy markets. Our responsibility is to keep the system efficient, effective and resilient — not only to technical and economic shifts, but also to shocks and, of course, political interventions.

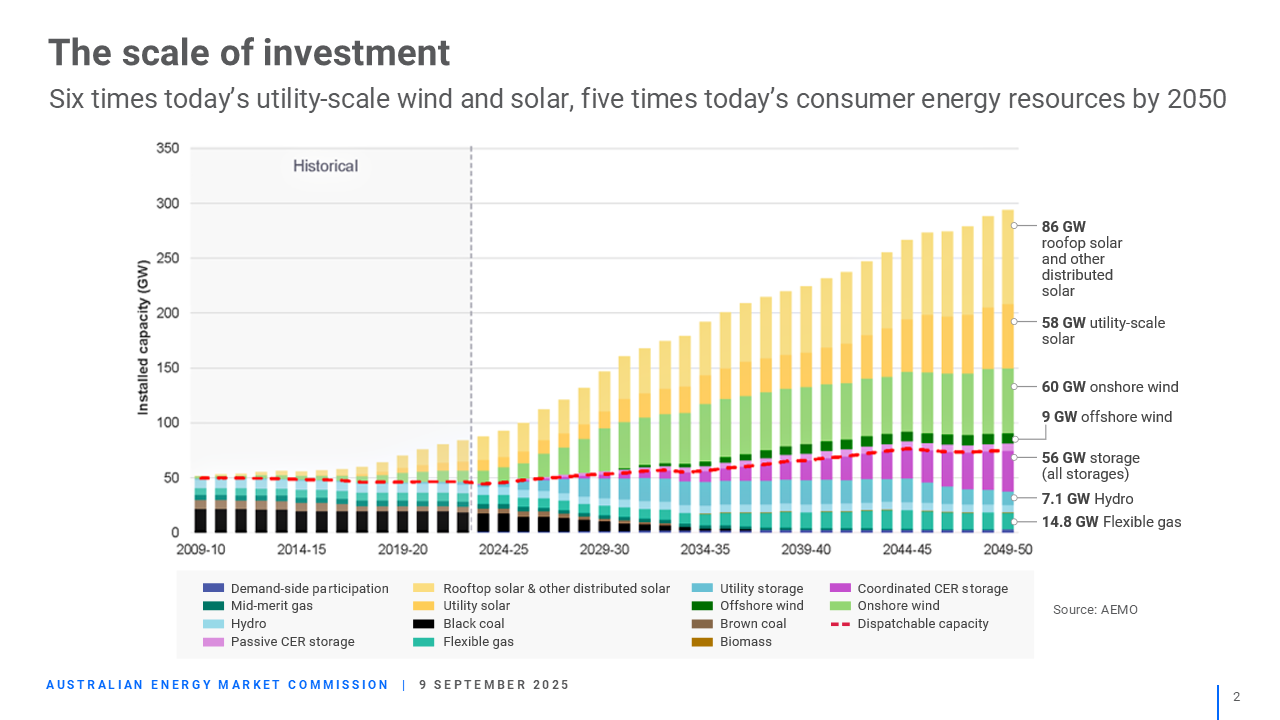

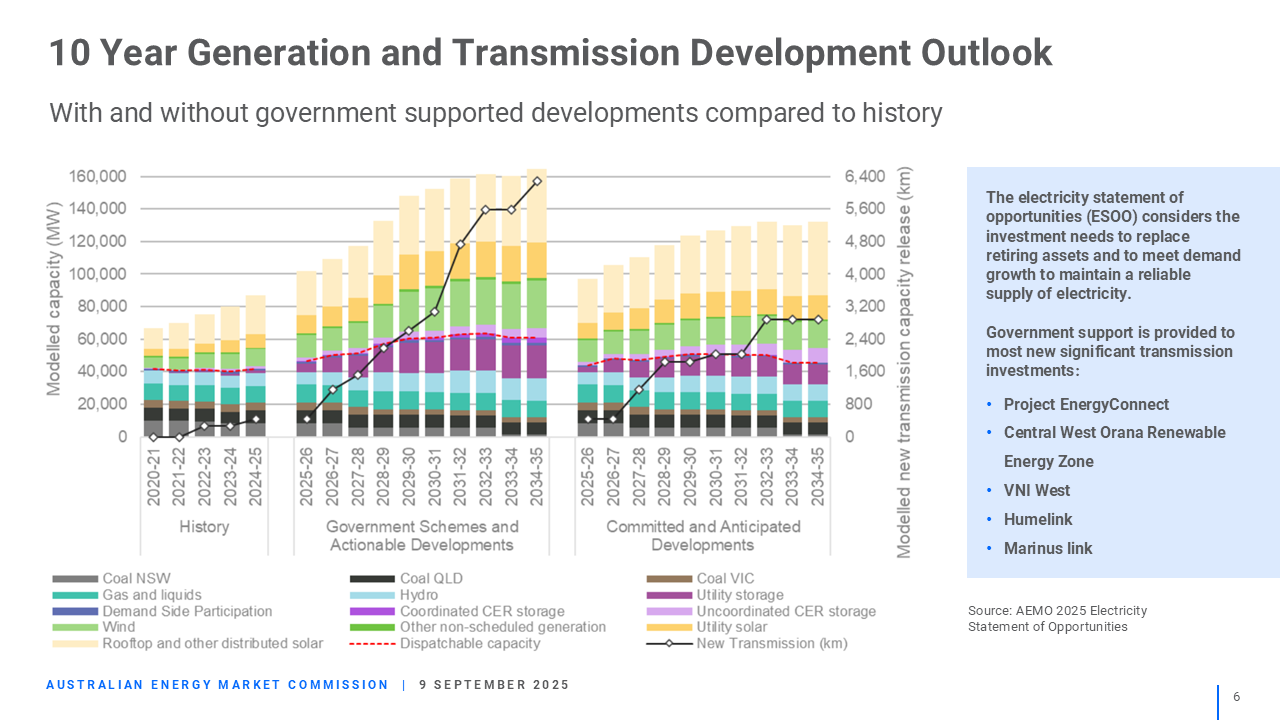

The scale of investment required to reach net zero by 2050 is enormous. New renewable generation is not always where the old coal generators were. That means investment in transmission — our interconnectors and networks — is essential.

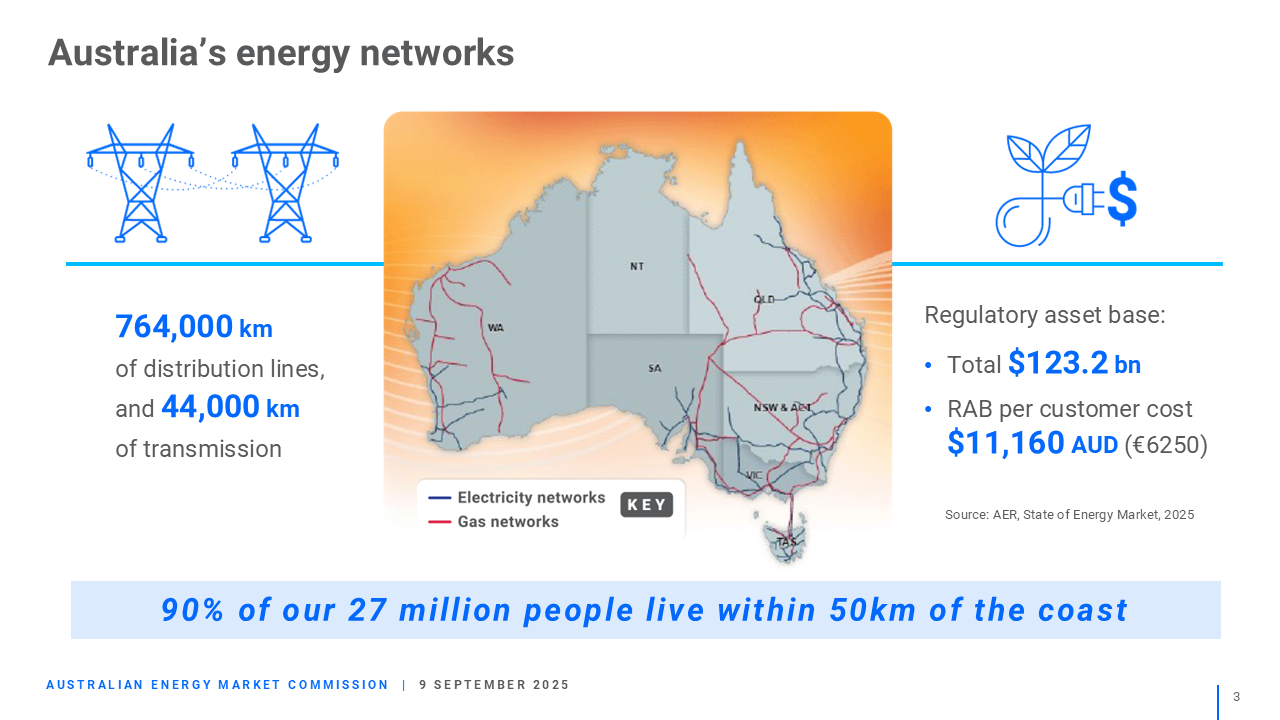

Australia is a federation of six states and two territories, spread across a vast continent. Our nearest neighbour is hundreds of kilometres across the sea. So when I speak of “interconnectors,” I’m referring not to international links, but to the transmission connections that cross state borders within our national market.

We actually have two distinct power systems. On the east coast, the National Electricity Market, or NEM, is an energy-only market spanning five states. On the west coast, where I live, the Wholesale Electricity Market operates as a capacity market.

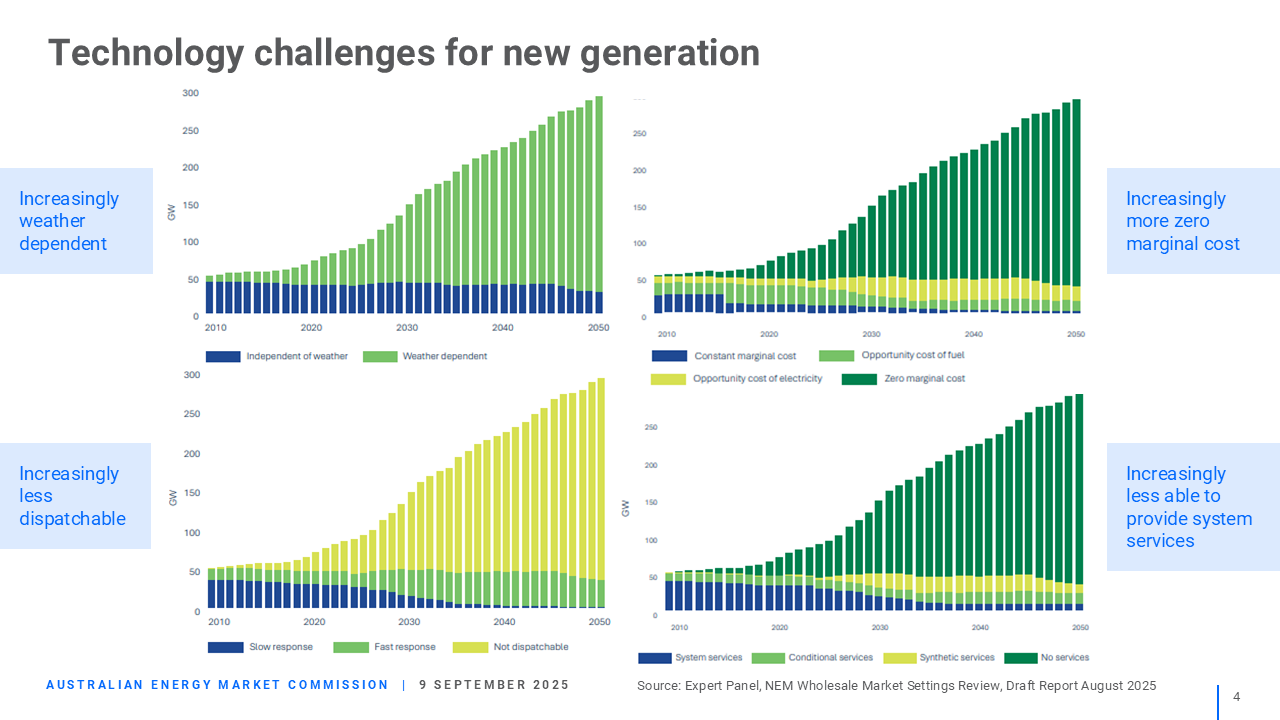

My comments today focus mainly on the NEM, but neither model — energy-only, or capacity — provides a smooth path for variable renewable energy and batteries without careful reform given the changing technological and economic challenges.

In the NEM, new interconnection is essential if we are to deliver renewable energy to consumers. Yet, while the need is clear, the process of getting these projects delivered remains fraught.

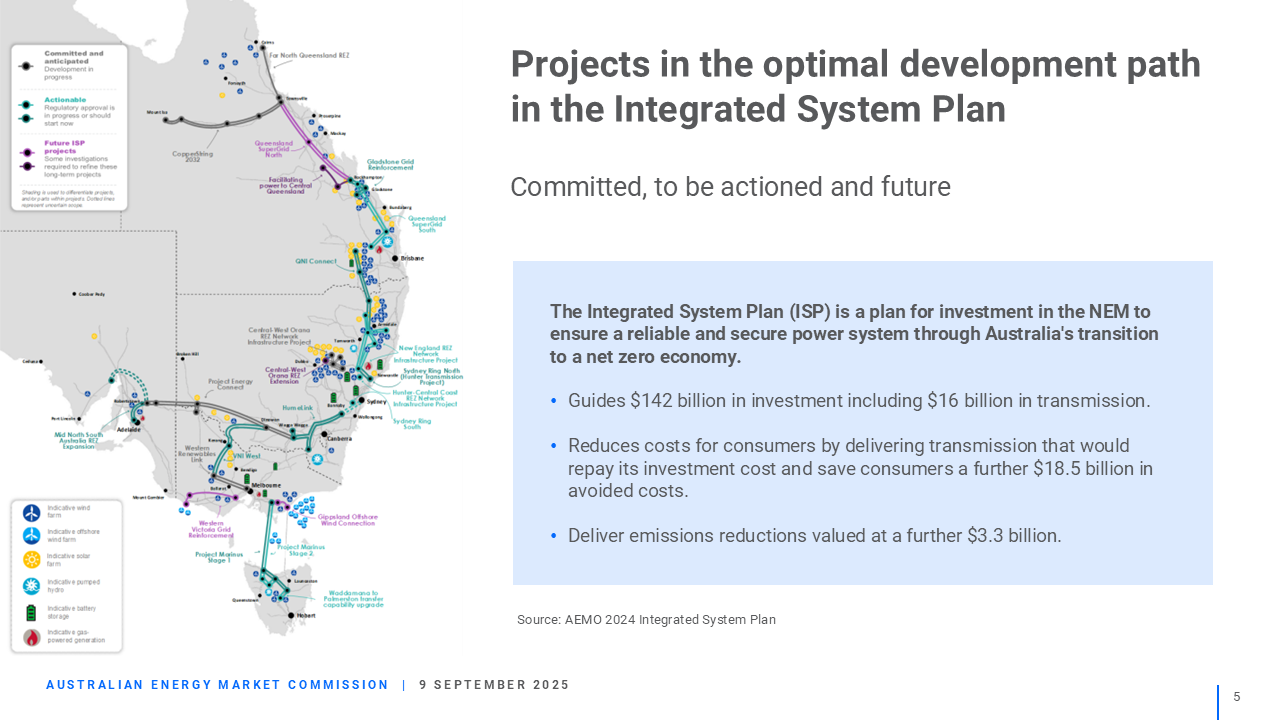

A few years ago, we introduced a major reform: the Integrated System Plan, or ISP. This plan is developed every two years by our market operator. It sets out the optimal mix of generation, storage and transmission needed over the next two decades to meet policy, reliability and security goals at the lowest cost. Importantly, it allows us to look beyond individual projects to see the whole package, and it provides the “hook” for transmission providers to begin the regulatory processes needed to recover their costs.

The ISP has been a game-changer. But challenges remain — and i will touch on a few here.

The ISP may show clearly that a package of transmission projects delivers the greatest net benefit to consumers, but under current rules each project must also test its individual merits. This slows things down, provokes opposition, and adds risk and cost.

Now, of course, oversight is essential. Projects must still be scrutinised for efficiency. But the way our process is structured means that even projects identified as part of the optimal plan face fresh battles to prove themselves. That is duplication, and duplication costs money — ultimately borne by consumers.

Financing is another sticking point. Our incentive-based regulation delays recovery of revenue. This creates cash flow problems, depresses returns, and slows final investment decisions. We’ve made some improvements in recent years, but the scale of the current build means risk is increasingly asymmetric. Incentive mechanisms that penalise cost overruns — even when efficient — deter investment in precisely the projects the nation most needs.

So while our framework has served us well, it is now adding unnecessary friction. And in this transition, delay itself is costly: costs are going up and the benefits of low cost generation are delayed. The longer it takes, the more consumers pay.

Both state and federal governments in Australia are stepping in with support for big projects — generation as well as transmission. This support can be direct or indirect through concessional finance or renewable energy hubs that smooth the path by coordinating planning, approvals, and even revenue support.

Although necessary to address some cash flow and cost recovery uncertainty and risk for big transmission projects, these processes can be slow.

Like other nations around the world these issues can be further frustrated when a project crosses state borders and the benefits do not flow directly to customers in the funding jurisdiction. And, exit strategies are needed to avoid crowding out private capital.

So what’s next?

Well, clearly we need to streamline regulatory processes. Duplication must go. Oversight should focus on efficiency and delivery, not repeatedly revisiting the basic need.

We need to address lingering issues in the regulatory regime that add unnecessary cost and risk to large projects in the national interest. Regulation should not be the reason funding its difficult or slow.

And we need to consider a consistent framework and criteria for government funding that facilitates timely investment decisions and certainty about when support might be provided and when it will not.

The goal is clear: give investors the confidence to commit capital at the right time, in the right place.

There is also an important role for consumer energy resources — rooftop solar, batteries, demand response, and, increasingly, electric vehicles. These are the lowest-cost, lowest-emission resources available.

These resources also provide an alternative to large-scale investment and aid resilience.

When generation and demand can be matched locally, it reduces the need for additional upstream large scale investment and reduces the impact of climate change events that put security and reliability at risk. But to realise this potential, they must be integrated efficiently into the system.

We have started making these resources visible and dispatchable. We need to further stimulate the availability and reliability of these resources by rewarding customers and extend its use to relieve congestion on distribution networks.

Related to this is to provide flexibility under the regulatory framework to utilise new technologies to lower the cost of the energy delivery service. We must revisit outdated rules about what regulated networks can and cannot do. The boundaries made sense in another era, but they may now prevent efficient, overall lower-cost solutions.

Poorly integrated, consumer resources and EVs could exacerbate congestion and minimum demand problems. Done well, they could avoid billions in new investment, reduce emissions, and strengthen resilience.

Let me finish with some things we’re learning.

First, there is no silver bullet. Every system will grapple with the economics and physics of weather-dependent resources. The mix of market design, regulation and government support will differ across markets, but the need to adapt is universal.

Second, government support is sometimes essential — particularly in times of uncertainty. But it must come with clarity and an exit strategy. Otherwise, we risk crowding out private capital and locking in dependency.

Third, opportunities for resilience and efficiency lie everywhere — in transmission, in large-scale generation, in distribution, and in the consumer’s own rooftop or driveway. The right lens is always the overall cost to consumers, not the cost of one project in isolation.

Fourth, time matters. Delay is itself a cost. In fact, the cost of delay can be greater than the risk of moving forward with imperfect information. If we want lower-cost, low-emission energy for consumers, we must take a few calculated risks.

Thank you — I look forward to your questions and to continuing the discussion.